Uncaria tomentosa and Uncaria guianensis, better known as “cat’s claw,” could help with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) joint pain.

NOTE: Always speak with your doctor before adding herbal supplements or over-the-counter medications to your regimen.

What is cat’s claw?

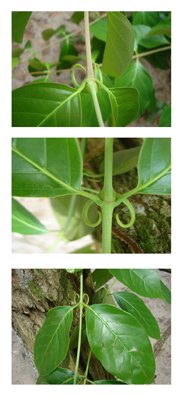

Cat’s claw, or uña de gato, is a woody vine that is indigenous to the Amazon rainforest, and is found primarily in tropical areas of South and Central America. It is named for the claw-shaped thorns on it that enable it to “climb” over 100 feet.

Most supplements are made from the Uncaria tomentosa (UT), though there is some research into differences between the two species. The bark and roots of the plant are used for liquid extracts, teas, capsules, and tablets.

The Incan people of Peru used cat’s claw historically for a range of purposes including stimulating the immune system, viral infections, and contraception. Because of this, women hoping to become pregnant may wish to avoid using this as an alternative treatment.

The NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health states that there have been few noted side effects when taken in small amounts. Potential side effects are less severe than typical medication side effects, which is part of the value of the plant. Side effects may include itching, rashes, or kidney inflammation. There is a case study where a person with lupus experienced kidney failure as a result of the remedy — furthering the above note that it is crucial to be transparent with your doctors prior to starting any new remedies. The NIH also share that there is not conclusive scientific evidence to use cat’s claw for health purposes. However, some studies have been conducted using participants that have rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We will explore those studies below.

Cat’s Claw in a double-blind clinical trial

Double-blind trials are crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of medications. In these trials, both the participants and the experimenters are unaware of the treatment (placebo or medication) that is being taken by a participant. This ensures that that neither party will accidentally or intentionally behave in a way that could influence the outcome of the study.

A study by Mur, et al., published in 2002 in the Journal of Rheumatology attempted to look at both the safety and effectiveness of using cat’s claw to help treat rheumatoid arthritis. Forty participants were involved in the study and they either received 60 mg of Uncaria tomentosa or placebo for 24 weeks. The participants reported on a number of RA factors to determine efficacy of the remedy.

Those receiving cat’s claw experienced significantly fewer painful joints, but they did not have less overall pain, swelling, or stiffness. For the next 28 weeks, all 40 participants received cat’s claw. While outcomes improved, they were not statistically significant. These findings made Rosenbaum, et al., 2010 to conclude that larger studies are necessary to conclusively determine the effectiveness of the treatment. The authors also looked at studies using cat’s claw to treat osteoarthritis (OA) and concluded that the remedy did provide sufficient benefit to be recommended for patients with OA.

Getting cat’s claw

There are a number of online retailers that sell cat’s claw. However, it is important to note that herbal medicines are not subject to the same rigorous testing and standards of traditional drugs. Testing of other herbal remedies have found that the packaging did not properly reflect the actual dosage or potency of the contained product.

One study found that packaging of parthenolide and feverfew leaf was inaccurate and that dosages could vary by as much as 150x and 10x, respectively. While these studies did not look at cat’s claw, they highlight the variability and lack of standards in the industry. Again, it is pertinent to speak with your doctor before starting new herbal supplement or medication.

How does cat’s claw work?

Research by Aubert, V, et al., 2000 illuminated the role of tumor necrosis factor alpha or TNF-alpha (TNFα) in chronic inflammation. TNFα is a cell signaling protein, or cytokine, able to induce fever, apoptotic cell death, inflammation and more. Because of this research and other prior work by the authors, Sandoval et al, 2000 examined how cat’s claw and TNFα would interact. The researchers found that cat’s claw suppressed TNFα by 65-85%. However, it is important to note that this research was done on cell cultures, not on humans.

Cat’s claw was also tested as an antioxidant, protecting the cell cultures from free radicals. In the study, 1,1-diphenyl- 2-picrilhydrazyl (DPPH, 0.3 M) and ultraviolet light (UV) light were examined. The researchers found that cat’s claw was an effective scavenger of the free radicals, protecting the cultures from DPPH and UV irradiation-induced cytotoxicity.

Similar with the study examining effectiveness above, additional research is needed to determine appropriate dosing for cat’s claw.